☄︎ ⌇Even the Sea is Broken⌇

حتى البحر مكسور

Published

Contributors

Razan is a Palestinian artist and teacher based in Tiotiake/Montreal. Her films work with the material aesthetics of appearance and disappearance of indigenous bodies, narratives and histories in colonial image worlds. She often works with sound-images to infiltrate borders that have severed us from the land. Her films are both ghostly trespasses, and seeping ruptures, […]

Samira Makki is a PhD student in Film Studies at the department of Art and Media Studies at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU). She is interested in the notion of the militant image, the depictions of belonging in film, and the rapport between politics and aesthetics. Her writings appear in Frames Cinema […]

Razan AlSalah “Your Father Was Born 100 Years Old, and So Was the Nakba” (2018)

This essay probes the ways in which returning to Palestine is imagined in Razan AlSalah’s two video works Your Father Was Born 100 Years Old, and So Was the Nakba (2018) and Canada Park (2020). In foregrounding the refusal of configurations substantiated by state concessions and normalisation treaties, the article treats loss as central to the manifold rehearsals of return. In AlSalah’s work, loss is understood not as becoming less, but rather as a proposition for becoming otherwise. Here, the practice of loss is explored through the glitch as both a conceptual framework espousing opacity and a pragmatic tool engaging pixel breaks. Rather than reducing the glitch to a mere erroneous aesthetic, the article underscores the active capacity in encountering a glitch or deliberately engendering it by exploring the tensions between colonial imageries reproduced in digital maps, and, in contrast, montage as AlSalah’s tool for intervention. Finally, the article serves as a theoretical experimentation with what I call “dialectical poethics,” which reads the filmic return through loss as an attempt to go against linearity, intelligibility, and finality, yet insists on a materialist grounding of the glitch as a method that is historically situated rather than always-already emancipatory.

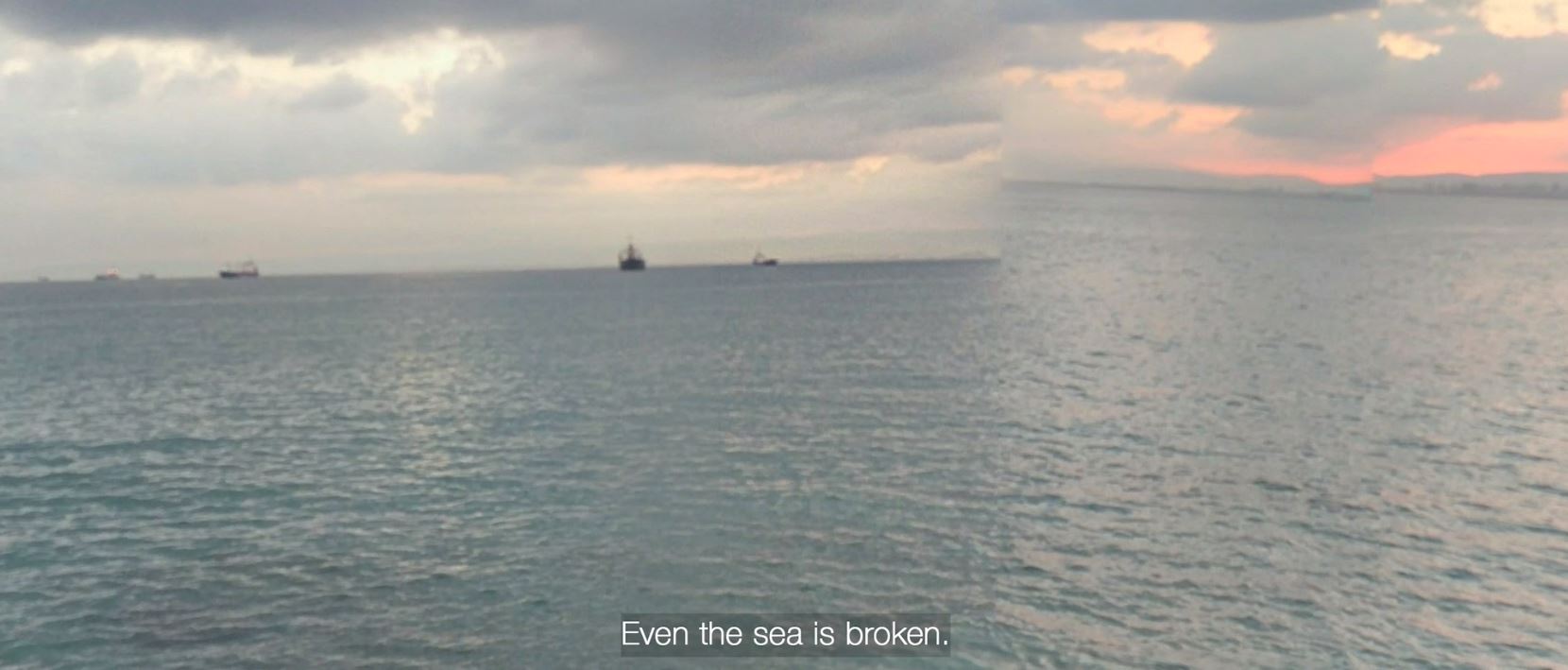

“Even the sea is broken, there is no escape” – a voice echoes softly, in disbelief, over an image of 7aifa’s sea retrieved from Google Maps in Street View. 1 Razan AlSalah’s Your Father Was Born 100 Years Old and So Was the Nakba or yfwb100yo (2018) follows the reincarnation of AlSalah’s grandmother Um Ameen, a first-generation Palestinian refugee, as an orange Pegman navigating the streets of Palestine’s 7aifa. 2 A flat figure, Um Ameen’s avatar searches for a home from which she was forcibly displaced in 1948, and a son, Ameen, whose sole memory of the place is of himself riding his bicycle on a balcony overlooking the sea. Broken pixels translate into an ill-stitched image of what appears as a broken sea, which further embodies a fragmentation protracting through generations of Palestinians who have been violently displaced and systematically denied a return to their homeland. To “jump in”, as AlSalah’s video begins, reveals a sense of return as free falling. Um Ameen is unsure of where to start the journey and is just as sceptical about where to end it, if she must. Here, return is fraught with disjointed routes, illegible street names, shrinking skies, and broken seas. In other words, return is configured through loss, as loss.

In her essay titled “To Have Many Returns: Loss in the Presence of Others”, Rayya El Zein (2020) speaks of return as “a practice of listening to loss”, one which, in its multiple rehearsals, invites us to consider “our sensing of each other differently” (pp. 44, 43). In sifting through the many layers which returns hold, El Zein opens her essay with a direct reference to the failure of peace accords, and congruent concessions, in safeguarding the right of return of Palestinians to Palestine. Informed by this betrayal, she invites the reader to consider return as manifold. Hence, while insisting on the unwavering right of return to one’s land, the means by which return is imagined – film being one of them – are expressed as multidimensional. Therefore, the fracturing of 7aifa’s sea exemplified in AlSalah’s video challenges superficial readings of visual material and specifically unsettles the conspicuity assumed in images of return. In what follows, I explore two of AlSalah’s short videos, yfwb100yo (2018) and Canada Park (2020); their significance lies partly in how they address return vis-à-vis loss, conceived here not as becoming less, but rather as “a different being with” (El Zein, 2020, p. 47).

Your Father Was Born 100 Years Old, and So Was the Nakba – orange Pegman commencing the free fall in 7aifa. Courtesy of Razan AlSalah.

Glitching as Dialectical Poethics

In exploring AlSalah’s rehearsals of return through loss, I first propose a poethical reading of her work, building on – but also at times break- ing with – Denise Ferreira da Silva’s proposition of a “Black Feminist Poethics” (2014). For Ferreira da Silva, poethics provide a speculative tool which dissents from colonial delineations of thought by rejecting “the transparent trajectory of the subjects of universal reason and of its grip on our political imagination” (p. 82). Because Ferreira da Silva insists on not delimiting her quest, I attempt to borrow, albeit carefully, from the expansiveness of her approach to think with Palestine. In reading AlSalah’s contention with loss through Ferreira da Silva’s poethics, I pay close attention to the latter’s kernel attributes of ethical responsibility and poetic candour, both of which are essential to reimagining the different returns to Palestine.

My reading of AlSalah’s method is twofold. First, it is through the potentialities of being and knowing enabled by poethics that I seek to consider AlSalah’s videos as positing a “reflective practice” (Ferreira da Silva, 2018, p. 4) which constantly negotiates its formal components and symbolic references. This relates to the notion of self-reflexivity, which Mike Wayne explains in Mar/ism Goes to the Movies (2020) as “the ability of cultural works to reflect on their own conditions of production and/or reception and/or their status” upon which “certain habituated meanings and expectations have accrued” (p. 127). Yet, as Wayne makes clear, self- reflexivity does not always yield politically engaged or radical accounts. Here lies the necessity not only to attend to the “otherwise” that AlSalah conjures in her images of return, but to further analyse the method with which this otherwise, through loss, is enacted. This is where the glitch is taken up for its poethical capacity to break with consistent, legible, and linear arrangements of return. In the neoliberal realm of represen- tation, Palestinians are made to incessantly negotiate their existence within a logic that attempts to either annihilate them or assimilate them into what Ferreira da Silva and Rizvana Bradley (2021) have termed “the ordered world” that “is supposed to be knowable” and which “all the common can comprehend” (p. 3). To dwell in this “ordered world” (Ferreira da Silva & Bradley, 2021, p. 3) essentially ties one’s visibility to an onto-epistemological framework in which justice is conceived based on evidentiary material. Similarly, various images from Palestine continue to feed into a certain mode of visibility which configures Palestinian bodies always-already as evidence. Clearly, this does not take away from the importance of documenting the atrocities incessantly committed against Palestinians, nor is it meant to domesticate the rhetoric around revol- utionary struggle and the necessity of its militancy. It is rather meant to complicate the deterministic function of such footage and its inexorable restrictions as long as it arises in normative discussions on justice and operates within the existing “colonial juridic-economic architecture” (Ferreira da Silva, 2014, p. 90).

How to recall the site of the wreck without having its violence feed into the logic of the expected, the ascertained, the commodified? Images, according to W. J. T Mitchell (2005), appear in specific “structures and historical events”, which allows us to consider them not as mere “objects of evaluation” but rather as “sources of value” (p. 83). This means that images that serve evidentiary ends are ascribed an exchange value that primarily depends on their decipherability. Therefore, any defect that risks the image’s readability compromises its significance as a commodity evincing evidence. Against that, loss is explored in this article vis-à-vis images of return that disrupt this extractive logic of visual economies where value is contingent upon discernability. To do so, I aim to recuperate dialectics as a method that permits thinking with poethics through a bidirectional “movement that conceals and confronts” (Ferreira da Silva, 2020) when reimagining returns to Palestine. Specific to AlSalah’s work, I situate such dialectical poethics as the theoretical frame- work upon which glitching, as an expression of loss as well as return’s modus operandi, aptly materialises. By referring to it as such, I under- score the active process of encountering or enacting a glitch so as not to reduce the latter to a mere aesthetic accident or a failure of a flow begging to be repaired.

Poethics is an open field that allows us to reconfigure being as constant becoming without reducing “what exists – anyone and everything – to the register of the object, the other, and the commodity” (Ferreira da Silva, 2014, p. 90). However, in thinking with Palestine, it might not be entirely possible to contribute to any speculations on return if not addressed dialectically. Instead of confining the discussion to “momentary resolutions at each instance according to an intention mediated by a given context” (Leeb et al., 2019), dialectical poethics emerges as crucial to grasping the affinity between Black and Palestinian struggles on the grounds of shared emancipatory politics that considers oppression and, consequently, modes of resistance to it as structural rather than situational. This compels a laborious process which demands that we rethink our concerns and realign our commitments as we establish zones of opacity that do not simply claim disappearance for disappearance’s sake. Rather, these acts of disappearance diligently work against the carceral logic underpinning ocularcentric economies that have systematically insisted on othering particular bodies, be they Black or Palestinian, so that they remain knowable, measurable, and controlled. As such, AlSalah’s filmic glitch is configured as a poethical tool that operates dialectically; it first confronts the “instantaneous compositions” that Ferreira da Silva (2016) refers to, and attests to the historical affordances as well as contradictions upon which its speculative potential is probed against colonial violence and its tacit and tactile forms of domination.

Consequently, I engage both the conceptual and pragmatic facets shaping the glitch-as-process in AlSalah’s videos, particularly in her reconfiguration of digital maps. In Hanan al-Cinema: Affections for the Moving Image (2015), Laura U. Marks suggests that today’s algorithmic structures, which the glitch has the potential to unsettle, are inseparable from oppressive practices that manifest through “surveillance and con- trol” (p. 239). This means that in countries which utilise ongoing despotic measures, many artists have espoused subversive methods that invest in “the breakdown of the code [rather] than in its well-functioning state” (p. 239). Referencing the work of media artists from Arab countries, Marks differentiates between the glitch as an “expressive quality” (p. 251), and that which results from issues related to compression or transmission that depend respectively on codecs and electrical grids. As such, she makes clear the distinction between the glitch that is engendered on the level of production, and that which occurs during processing, transmission, and display. In this context, I approach AlSalah’s work for its contemporary significance to the practices of various Arab media artists that engage notions such as “selective memory and forgetting” and contribute to “an examination of archives” (p. 253) by centring the role of the glitch in forging such attempts.

To do so, I foreground Rosa Menkman’s (2011) take on the glitch as a “procedural entity” with the capacity to interrupt the linearity ascribed to the “procedural flow” (p. 30) upon which the logic of digital media hinges. Rather than the glitch’s coming across as a tech mishap or a bug, Menkman considers its “critical potential” and its challenge to “the norms of techno-culture” (pp. 27, 8), and, by extension, its embedded politics. Similarly, Legacy Russell (2020) posits the glitch as a site for “perpetual motion” which “brings new movement into static space” (p. 74). Yet, the static space she speaks of is only tangible for those of us who come face to face with digital apparatuses exclusively as users. This reiterates the superficiality with which one might experience the pseudo-transparency assigned to any technology, reinforcing a “see-through” vantage point that flattens the medium with which we are engaging, so that any error is interpreted as sheer dysfunction (Menkman, 2011, p. 16). Against that, I see the glitch in AlSalah’s videos as that which breaks the predictability, transparency, and control often ascribed to digital media. Rather than treating the glitch as counterintuitive, I consider its potential to become “a vehicle of resistance” which allows us to locate ourselves “inside of brokenness, inside of the break” (Russell, 2020, p. 112). This paves the way for conceiving the glitch as an experimental undertaking that bolsters the many and multidimensional practices of return emanating from within the break, further echoing El Zein’s (2020) insistence on the elasticity and capaciousness needed to navigate “the practice of return as a political process with radical potential” (p. 44).

Returning as Anonymous X

In yfwb100yo (2018), Um Ameen returns to 7aifa as an orange Pegman whose featurelessness is anything but arbitrary. As explained by Ryan Germick, who was once leader of the team that experimented with Pegman’s various forms, the passepartout appeal of Pegman aims to “pare down to the bare elements that need to be there to communicate”, and not to trigger any sort of overt association with it (Sharrock, 2013). However, it is because of this flat physiognomy upon which the logic of “anyone can be orange” operates (Sharrock, 2013), coupled with the mobility of spaces and the malleability of scales which Google Street View supposedly allows, that Um Ameen could return. By virtue of her orange skin, Um Ameen returns without having to stop at a checkpoint, without facing abrupt roadblocks, and without being harassed by IOF soldiers or Israeli settlers. She returns as anonymous X.

Yet, this anonymity itself is an enactment of a twofold violence: the erasure of historic Palestine and the normalisation of colonial visuality. In “Navigation Beyond Vision”, Doreen Mende and Tom Holert (2019) depart from a purposely loose demarcation of what the practice of navigating a digital space might entail. They stir up the complexity of navigation, its apparatuses and infrastructures, beyond what appears by way of computer-generated images. A simple search for the etymology of the word on the Online Etymology Dictionary (2019) suggests that “navigation” appears to come from Latin navigare, “to sail, sail over, go by sea, steer a ship”, a combination of navis meaning “ship” and the root of agere meaning “to set in motion, drive, drive forward”. In a way, the act of navigation holds the promise of a destination. Yet, just like the dangers hidden in the belly of the sea, navigating the “digital oceania”, as Mende and Holert (2019, p. 2) call it, is also susceptible to the hazards of algorithmic waves, their perturbation, and their possible crash.

Um Ameen begins her journey at a crossing. Pausing at a zoomed-in frame of a two-way traffic sign, she delivers a fact-check: “This is the crossroad of the British Colonel William Stanton Street, and Burj Street. The crossroad of history, between colonialism and Palestine”. Um Ameen remembers, and this very memory disturbs the paltriness imbuing Google’s Pegman. However, her metamorphosis is not celebrated, nor is it deemed the final form in which she returns. In an interview with We Are Moving Stories (2018), AlSalah stated that the rationale behind employing Google Street View to enact her grandmother’s return “came out of necessity” since “it is the only way she can see Palestine. It’s the only way I can access the land too”. This attests to the viability of dialectical poethics as a method that allows one to probe the inter- dependency between the necessity that first led AlSalah to turn to Google Street View, by considering another necessity which prompted her consequent intervention by way of montage. Here, AlSalah’s aesthetic tactics have come to engender intentional breaks and to further expose existing ones. She locates, right in those cemented cracks on which the two-arrow sign barely holds, the cracks in history, ones that Google Street View has strived to eradicate with its image-processing protocols.

As Mende and Holert (2019) remind us, although navigating the digital realm is facilitated by way of image-led interfaces “in perpetual motion”, the process itself is informed by various political, cultural, economic, and legal conditions that “codify, enforce, (and constantly transform) the navigational condition” (p. 2). In other words, while regular tech-checks and proactive upgrades might enhance the visual configuration of online spaces such as that of Google Street View – the latter being AlSalah’s main material for intervention – they are not the sole factors that come into play as far as navigation is concerned. This raises a significant question concerning archetypes of progress and access vis-à-vis navigation, and further invites us to challenge the intelligibility assumed in the “clarity of vision and reliability of data” (p. 2).

Your Father Was Born 100 Years Old, and So Was the Nakba – cracks in history. Courtesy of Razan AlSalah.

As such, montage is the tool that AlSalah deploys to strike back at the violence of colonial coordinates. While navigation rests on the principle of perpetual unfolding, montage has the capacity to reframe, to dwell in, to freeze or disrupt motion. While navigation seeks “boundless and border- less” figurations (Mende & Holert, 2019, p. 2), montage is articulated in its capacity to see in “the excess of the seen […] making the moments between frames palpable” (Mende, 2020, p. 8). It is exactly here that we can locate the dialectical tension between navigation and montage. Finding herself on “Shivat Tsiyon” street, Um Ameen asks, “Why did you bring me back here? When I can’t feel this place”. “Shivat Tsiyon” is Hebrew for “Return of Zion”, which in the video is sarcastically referred to as “Liberation Street”. Right there and then, Um Ameen realises that the 7aifa she has returned to as Pegman is not the same one from which she was forcibly displaced. Consequently, she is made unable to navigate 7aifa not only spatially, but also symbolically. Carefully woven into Google Street View’s “smooth transitions” (Google Maps, n.d.) is a concealed violence upon which an online space is conceived and navigated, a violence that surely has its roots in the same colonial logic that informs and shapes movement and mobility in the offline spaces we inhabit corporeally. This is where the abstraction of “providing momentary resolutions” (Leeb et al., 2019) fails us, in that it reminds us that while some navigational ventures are bound to the shores of the digital, others are designed to end – rather than accidentally result – in shipwreck.

In this sense, Um Ameen is actively made unable to locate the home from which she was displaced, nor the balcony on which her son spent his childhood. She is made unable to read signposts which have been replaced with texts in Hebrew, and unable to recognise those who could have been her neighbours. She is made unable to “feel this place”. It is at the height of this affective schism that Um Ameen recognises her alienation, which then ushers in her complete disorientation. The latter culminates in a visual overflow saturating her visual field. Images in 360° are sped up and repeated, forming a nauseating movement that accentuates Um Ameen’s delirium. In the midst of it all, she exclaims, “I can’t even see it, they’re showing it to me”. This outward projection of the act of seeing breaks the assumed synchronicity between seeing and knowing. Perplexed to see through Pegman’s colonial eyes, Um Ameen’s memories resurface by way of agitated speech and overlaid photographs to disturb the disembodiment with which Pegman navigates 7aifa.

AlSalah breaks with the linearity assumed through navigation by engaging layering as her method. On the one hand, the layering of images over others questions the principle of real-time associated with moving through and between space qua navigation. Images of historic Palestine in black and white are superimposed over Google Maps’ computer- generated images, rebuffing the Zionist myth which claims that this place was unpopulated before 1948. It begins with a photo of a well laid atop the same intersection that marked the crossroad between Palestine and colonial conquests. Unable to locate where her father Ameen was born, AlSalah pronounces this well his place of birth, as well as that of the Nakba’s; they were both, in this pronouncement, born 100 years old. A “time worm hole” as AlSalah calls it (We Are Moving Stories, 2018), this historic well disrupts the colonial logic of Space/Time. By so doing, montage allows Um Ameen to exist in “transversability”, which, according to Ferreira da Silva (2014), is “the moving back and forth to different points in time” that builds on “connections that precede time and space, but which operate in time and space” (p. 93). Here, one can pinpoint both the overlaps as well as the discrepancies in Um Ameen’s experience of forced displacement, that of her son Ameen, and of AlSalah herself, albeit without having one be tantamount to the other.

This superimposition of images is coupled with sound bites of personal accounts that interrupt the debilitating silence with which Pegman navigates 7aifa: 7aifa, 7ummus, ba7r (sea), 7abibi (my beloved). Um Ameen’s emphasis on the letter H/7/ح as she enunciates the different words that comprise it reverberates loudly in a place where Arabic letters, and their sound, have been erased. Um Ameen finds solace in repeating her son’s name, Ameen, whose recurrent utterance guides her as a mantra would, with the familiarity it carries in a space rendered so strange, a familiarity that is poetically wedged in the Arabic meaning of the name Ameen, a custodian, one who can be trusted. In other words, the promise of return to Palestine will always be safe and sound in the hands of its entrusted custodian, its Ameen.

Hence, Um Ameen returns to refute the myth of non-existence together with her son as her companion, whose name imbues a silenced soundscape. This transversability achieved by way of layering, of both image and sound, allows Um Ameen to return to colonial Space/Time by taking on an ephemeral form. Her somatic memory, which haunts the bareness of her orange skin, refusing to forego or to forget, is expressed through bits of oral history and photographs from historic Palestine, reiterating what Ferreira da Silva (2014) refers to, following Hortense Spillers, as the narrative “of the flesh” (p. 91). Spillers’s essay “Mama’s Baby, Papa’s Maybe: An American Grammar Book” traces the very materiality of violence enacted upon Black flesh. Her use of the term “flesh” does not oppose the conception of a Black “body”, rather it engulfs it. According to Spillers (1987), “before the ‘body’ there is the ‘flesh’, that zero degree of social conceptualization that does not escape concealment under the brush of discourse, or the reflexes of iconography” (p. 67).

Hence, the flesh stands for material relations that are discursively mediated yet that outlive the ephemerality of bodies. This “flesh”, as Alexander G. Weheliye (2019) puts it, is “both opposed to the body and in parasitic relationship to it” (p. 238), which then renders it an interstice that rejects certain modes of belonging and embraces “alternate modes of being […] albeit without erasing the traces of violence which give rise to them” (p. 239). The dialectical relation between Um Ameen’s ephemeral body (as the orange Pegman) and her historical flesh (as a forcibly displaced and colonised subject) comes to the fore in AlSalah’s editing technique. The footage that AlSalah employs upsets the flatness of post- racial avatars as well as the compliance of digital maps, both of which dilute the violence rooted in propagating colonial visuality. As such, photographs from historic Palestine coupled with Um Ameen’s speech intervene as mediating aesthetics to contend with a history that attests to the memory of the flesh. In keeping with Weheliye’s (2014) engagement with the flesh as para-ontological, the former is conceived – following Spillers – as the site where “the lacerations left on the captive body by apparatuses of political violence” are marked (p. 40). Yet again, the prefix “para” allows for an apposite (rather than opposite) articulation of the flesh as that which also holds the capacity for a potential emancipation, or in the words of Weheliye (2014), “the flesh stands as both the cornerstone and potential ruin of the world of Man” (p. 44).

Your Father Was Born 100 Years Old, and So Was the Nakba – “Even the sea is broken”. Courtesy of Razan AlSalah.

To escape the stifling streets of 7aifa, Um Ameen requests to be escorted to the sea only to end up in the port of 7aifa, where she recalls boarding the British ship which transported her and other Palestinians to Lebanon’s Beirut in 1948. Her narrating voice is coupled with an archival image of the colonial ship fading in haste. There, Um Ameen strolls around and finds herself on one of 7aifa’s present-day ships among tourists filming a military show led by the settler-colonial Israeli navy. The 360° view from the midst of the ship’s deck brings about a feeling of enclosure, heightened by the pointing cameras, where we are no longer sure if Um Ameen is the one being captured by their shutters. Disappointed and enraged, she once again asks to be transported to the sea, where she spends the briefest of time. “The sea is all we have left” is what Um Ameen first utters by the water. The image of 7aifa’s sea provided by Google Street View appears as broken. Simultaneously, an artefact hangs from the sky, but it does not seem to trouble Um Ameen. Her encounter with these glitches becomes her cue to exit. “I must return”, she cries out. Um Ameen sheds her orange skin and fades into the black streak, with her final words being “there is no escape”.

Um Ameen sees the glitch first as a warning sign, then as a portal. Intervening through montage, AlSalah met the glitch with attentiveness rather than dismissal. In her encounter with broken pixels, and the extension of this break to 7aifa’s sea and sky, AlSalah has contended with “accidents and errors […] as new forms of usability” (Menkman, 2010, p. 8). Leaping into the unknown does not mark the end of Um Ameen’s journey of return. Instead, it is proof for its multiple rehearsals. “There is no escape” from returning; however, departing each time from the materiality of the flesh, the glitch becomes an opportunity to return otherwise, an insistence on other ways, other forms.

Returning as Takseer

AlSalah returns two years later with a short video poem titled Canada Park (2020). This time, she attempts to return as herself, yet once again, by means of Google Street View. In this particular rehearsal of return, AlSalah’s virtual body experiences movement mediated through the body of a cyclist roaming Canada Park. Also known as Ayalon Park, Canada Park was completed in 1984 on the ruins of Palestine’s Latrun and its villages Yalo, Imwas, and Beit Nouba, which were razed to the ground by the Israeli occupation forces during the 1967 Six-Day War. According to Ghada Karmi (2010), Canada Park was built using tax-exempt donations by Canadian taxpayers to the Jewish National Fund (JNF), which was established in 1901 as a “non-state, para-governmental organization” (p. 2). The founding of the JNF played a central role in the expansionist aspirations of the Israeli colonial project through “green colonies”, as Ghada Sasa (2023, p. 223) calls them. Sasa (2023) traces JNF’s role in land grabbing, afforestation campaigns, and greenwashing in tandem with the systematic destruction and complete levelling of Palestinian villages. The lofty pine and cypress trees with which Canada Park’s opening scene is saturated were a strategic decision by the JNF to “Judaise, Europeanise, and dehistoricise Palestine” (Sasa, 2023, p. 220), which translates to the deliberate wiping of the area’s natural flora. As such, these fast-growing non-indigenous evergreens were meant to hide the ruins of the villages upon which these forests were built, and, by extension, to keep Palestinians from returning to their land.

Cruising the park with Google’s devoted cyclist, AlSalah interjects, “My eye has no iris, my eye is glass prism, excavating beyond the ruins, beyond the city of trees”. The Arabic word for “glass prism” as used here is takseer, which, in this context, translates to the refraction of light. However, takseer from kassar also means “to break”. This opening line both resonates with and complicates Um Ameen’s baffled line in yfwb100yo: “I can’t even see it, they’re showing it to me”. Keeping in mind her grandmother’s disconcerted attempt “to see”, AlSalah returns to openly break with the act of seeing itself. In photographic terms, the iris is the function that controls how much light enters the camera’s lens, hence regulating exposure. Having no iris, AlSalah’s eye works against the dyad of exposure/capture: exposure (exposing) and by extension capture both guide colonial expansions and define the camera’s basic functions. The camera, as Ariella Aisha Azoulay (2019) reminds us, has its roots in colonial conquests whose acts of plunder and expulsion are the backdrop upon which this visual tool has developed, thus aiding acts of dispossession, bearing witness to them, then consigning them to a past in which they appear as a fait accompli. This irreversibility attached to acts of exposure/capture in both colonial and photographic terms is challenged by Azoulay, who proposes that we tread very carefully the abundance and detachment which visual archives supposedly facilitate. As such, “excavating beyond the ruins” as AlSalah posits, demands that we recognise our own entanglement in reproducing the imperialist logic of “photographic events” that are treated as “representations of specific, well- designated objects, sites, events, and figures” (Azoulay, 2019, p. 361).

AlSalah’s intervention thus contests the logic of excavation itself, one that rests on systematic uncovering, grabbing, and possessing. Of course, Israel’s excavation projects on Palestinian land extend a colonial legacy inherited from their British predecessors. Published by the Palestinian human rights organisation Al-Haq, a recent report shows the twofold colonial logic of Israel’s archaeological projects. First is the selective, sporadic, and scattered excavations that Israel employs to justify its decontextualised findings through its forced control “over planning, zoning, and the mapping and surveying of archaeological sites by the military commander in conjunction with the Israeli Antiquities Authority” (Guillaume, 2022, p. 22). The militarisation of colonial archaeology does not only rest on exploiting, plundering, and appro- priating Palestinian heritage, but also heavily relies on the active erasure of indigenous knowledge by targeting and destroying historic sites that disprove the Zionist narrative. While Israeli excavation projects express the colonial desire to manufacture proof, AlSalah’s eye excavates not to uncover, but to upset. As such, she goes against methods of excavation as empirical evidence and instead breaks, by way of montage, the logic of facticity with which a colonial imagery has built its cartography. More specifically, AlSalah’s video echoes Azoulay’s call to constantly negotiate the position from which we encounter and navigate archival material – here, digital maps – so as not to fall into “the triple imperial principle and its traps, set to ambush and lure us” (2019, p. 361).

Images from the 2007 March of Return to Latrun are overlaid on Canada Park’s present landscape. As we navigate hiking trails and archaeological monuments surrounded by an ever-infringing foliage, images of return serve to disrupt the one-dimensional imagery that Google Maps deploys in its simulation of historic Latrun. AlSalah’s technique of superimposing these fleeting images appears, as Azoulay (2019) would put it, as a practice of “unlearning” which refuses “the stories the shutter tells” (p. 26). In a way, Google Maps serves to prolong the process of exposure/capture since the imagery it provides must stay up to date to facilitate the navigation of virtual space. The imperial shutter, aided by navigation apparatuses such as Google Street View, never really ceases to operate.

Canada Park – March of Return. Courtesy of Razan AlSalah.

Here, AlSalah’s use of the archive and its layering on top of colonial imagery is, in Azoulay’s words, a rejection of “the rhythm of the shutter” (p. 27). This refusal of the colonial shutter is expressed by breaking (into) the levelled space of Canada Park, unsettling its contemporariness, and returning to it as a site from which thousands of Palestinians were forcibly displaced. Consequently, images that reflect (Google Maps) are confronted with images that refract (March of Return). 3 It is important to note my use of both terms reflection and refraction in their dialectical relation within the specificity of image-making processes. Images that reflect are those which reproduce colonial visuality whereas images that refract are those that potentially break with it. Both these notions are being used here with the awareness of their limitations.×

Trees have proven essential to the expansion of Israel’s colonial cartography. The use of green foliage to conceal its violence has been maintained by afforestation campaigns led by the JNF to lure tourists in by reinforcing the Zionist myth of “making the desert bloom” for as low as USD18 per tree. Transplanted over the ruins of Palestinian homes, these trees haunt all those who are complicit in expanding Israel’s settler- colonial violence. AlSalah builds on the trees’ symbolic capacity to haunt via carefully crafted auditory and visual tactics. As the cyclist’s camera tilts up, the green hue which comes to encroach onto the screen slowly begins to dissolve as though washing away Israel’s own greenwashing. The trees lose their colour and recede into undecipherable shapes by way of datamoshing. 4 AlSalah’s eye, which refracts, renders the crisp greenery almost obsolete. The trees that Israel missionises to “safeguard vital natural, historic, archaeological, and architectural sites” (Sasa, 2023, p. 223; original emphasis) by the deliberate spreading out of natural parks, promoted as contributors to public good, turn into speckled fragments that break up and disperse. Yet again, AlSalah is, in her words, “not from the public” for whom these seeds continue to be sown. In fact, she is denied return so that these very trees would live on. She is, as she puts it, “the undercommon”, which comes back to haunt.

AlSalah’s use of this term is not arbitrary. Throughout their various writings, Fred Moten and Stefano Harney have set the ground for this notion of “the undercommons” with which AlSalah experiments. In “A Poetics of the Undercommons”, Moten (2016) argues that in order to disrupt the ontology of nothingness to which Black bodies have been relegated and on which their value has been predicated, a new, para- ontological distinction between Blackness and Black bodies becomes pertinent. He departs from the notion of relative value by way of which the binary separating, and hence valuing, Black bodies has operated. To break this binary, the site of Blackness becomes that of “no-thingness” (as opposed to nothingness), which then refuses value (qua thingification and commodification) and becomes “a kind of general condition, which, […] everyone may access” (p. 29). Echoing Ferreira da Silva (2014), Moten opens up this zone of no-thingness to all those who refuse Being (as per the categories of the Human, the Universal, the Thing, the Valued). With that in mind, how are we to gauge the complexity informing such acts of refusal that emanate from the site of Blackness without reducing the latter to what might come across as abrupt configurations and extemporaneous renditions?

Canada Park – undercommons. Courtesy of Razan AlSalah.

While AlSalah identifies the zone of no-thingness and subsequently identifies herself within it, she nonetheless complicates her own positionality. Residing in Canada, she foregrounds the struggle of Turtle Island’s indigenous peoples and draws on the commonality between their fight and that of Palestinians against colonial powers. Opening her synopsis of Canada Park retrieved from her website, 5 AlSalah writes,

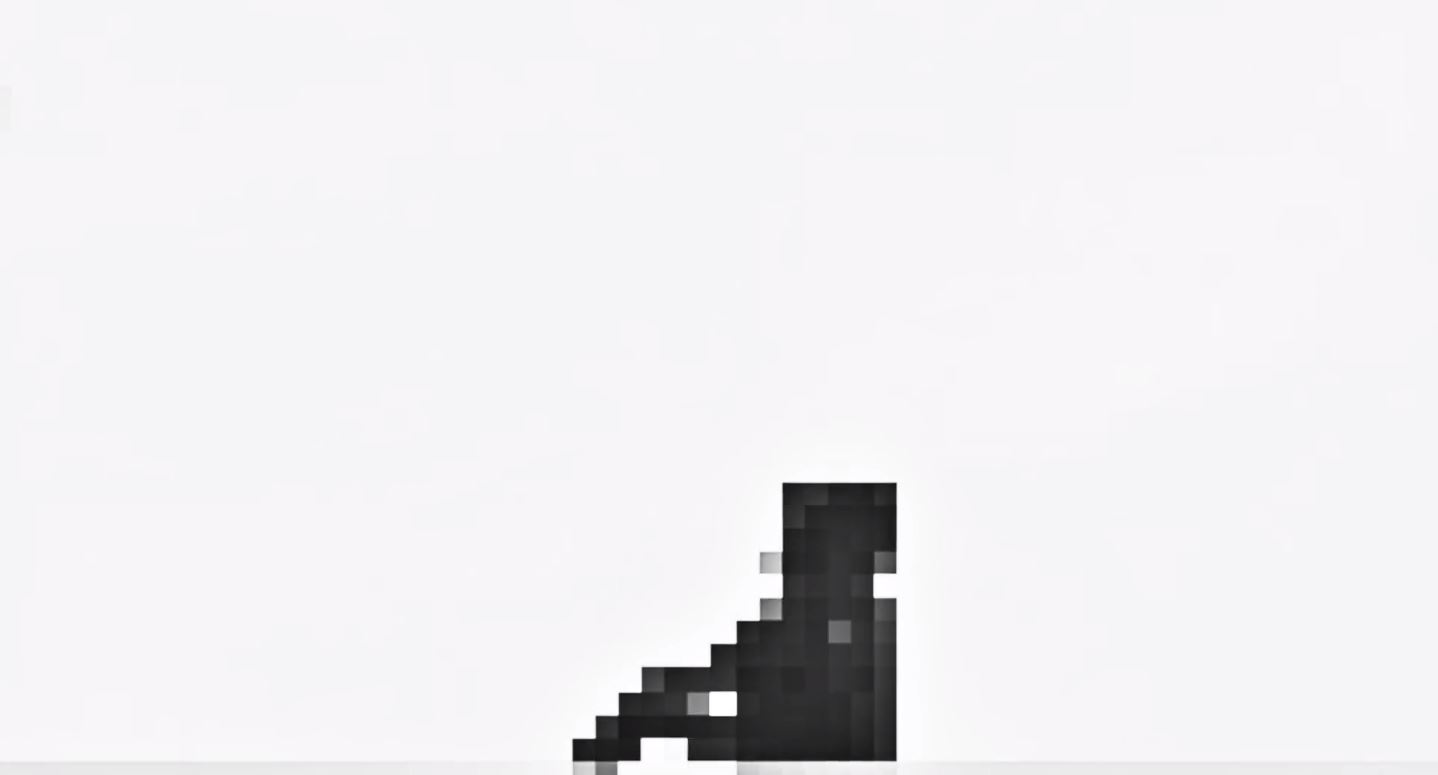

“I walk on snow to fall unto the desert. I find myself on unceded indigenous territory in so called Canada, an exile unable to return to Palestine”.

Transported from the green scenery of Canada Park to the snowy hills of an unidentified park in Canada, a figure dressed in black enters the frame. AlSalah zooms in on a silhouette pausing to face an enormous pole on which satellite dishes are mounted. The figure moves to the tunes of “Um Al-Ghaith”, Arabic for “Mother of Rain”, a folk chant with various versions across the Middle East and North Africa, which has been performed by indigenous communities to plead for rainfall in times of drought. Excommunicated as it were from the realm of the Civilised, the figure’s gesticulation is not to be picked up by the transmission technology which it confronts. The closer the camera zooms in to the figure, the more pixelated the latter becomes. Yet, these pixels are not prompted by, as one might think, low-resolution imagery; they are, rather, deliberately engendered onto the figure itself and are part and parcel of its production.

This is where the glitch becomes a tool that does not contribute to a devaluation per se, but rather throws into flux the logic of value in and of itself, insofar as decipherability as evidence is concerned. Here, the question of desire enters the scene. If we were to maintain, following Mitchell (2005), that images are also capable of wanting, and not only meaning, then we must ask, what does the glitch in AlSalah’s films want? Mitchell reminds us that what images want is not the same as the message they relay or effect they prompt, and that maybe, they are as confused about what they desire as the voyeur returning their gaze. But what if there was no gaze at all? Mitchell points to the difficulty of studying images where “the face as the primordial object and surface of mimesis” (p. 46) is absent. The glitched figure in AlSalah’s film is a visual critic’s worst fear, in that it threatens the very essence of personhood. Not only does this figure not have a face to gaze or be gazed at, it appears in the embryonic form of the digital image, as pixels. Instead of the image becoming a glitch, it is born a glitch; we may speculate that what the glitch might want is to not be an image, at least in the normative sense. From the outset, image-as-glitch perturbs the logic of legibility-as-value upon which evidentiary images are devised and commodified. In tandem with the ways in which Moten (2016) and Ferreira da Silva (2014) express Blackness as the site of no-thingness, the glitch becomes the tool that “unsettles the fallacy” with which images impose their authority vis-à-vis their assumed perspicuity (Ferreira da Silva, 2014, p. 84).

Canada Park – pixel-silhouette. Courtesy of Razan AlSalah.

In the same way that Blackness disrupts the relative value ascribed to split and separated bodies, the glitch in AlSalah’s Canada Park is an attempt to locate oneself in this zone of no-thingness. Consequently, the glitch becomes the site where the undercommons, exemplified by the pixel-silhouette, choose to (dis)appear. The figure stands as both a metaphorical as well as tangible reference to the deliberate refusal of indigenous people to appear as evidence. In so doing, they choose instead to dissolve into unruly and unfathomable data as they claim, through the glitch, their wilful “gestural withdrawal” (Moten, 2018, p. 243). Here, I would like to reiterate the risk of formalism to which the function of the glitch could be relegated. Generally speaking, value is threatened, yet not always defied, when a collection of pixels does not abide by the conventionally fundamental trait that defines an image, that is, its discernability. As Menkman (2011) shows, the glitch, like any technology, is not immune to the logic of capital. Never inherently emancipatory, the glitch, when designed as an end-product in and of itself rather than devised as a method to break and rearrange material and symbolic flows, loses “the radical basis of its enchantment and becomes predictable” (Menkman, 2011, p. 55).

Therefore, the self-reflexive trait of the glitch as that which interrupts “meanings and expectations” (Wayne, 2020, p. 127) must be posited as a site for experimentation which foregrounds the materiality of its own aesthetic, borrowing from the conceptual expansiveness that Blackness holds, all the while being aware of the dangers of reductionist takes that undermine the contingent history of struggles. As such, glitching could be thought of as a process which the undercommons – with whom AlSalah contends – seek and foster against colonial Space/Time, however differ- ently these rehearsals might play out. In AlSalah’s work, the glitch bears no essentialist trait; instead, it is located in the capacity of this “planned obsolescence” (Menkman, 2011, p. 8) to contribute to the different imaginings of return vis-à-vis their radical potential in forging a Palestinian political project beyond the confines of the nation-state.

Notes Against Finality

Throughout this article, I have attempted to engage AlSalah’s work as a poethic experimentation with returning through loss, as loss. Loss, here, has been formulated and experienced in the realm of the audiovisual and operated by way of the glitch as that which breaks certain image and sound worlds, a step necessary to generate others. AlSalah’s work rests within the growing site of experimentation which artists from Palestine have undertaken, further forging spaces of opacity as potential zones of disappearances. 6 Here, I underscore again the materiality of processes with which we make (in)visible; neither maps, in their quest to unfold, nor glitches, in their capacity to hide, hold any teleological function, which is why I have centred their dialectical relation without treating them as exclusive opposites to one another.

Because I see the glitch not solely in terms of pixel fissures, but also as a conceptual framework that further informs my take on return as an otherwise, I have attempted to pay close attention not only to the capacity of a glitch to conceal and break, but to the very ways it has been made to conceal and to break. This means that criteria such as clarity, decipher- ability, and resolution fundamental to the discussion of justice-through- evidence in the realm of liberal democracy have been called into question. In her essay titled “Toward a More Navigable Field”, Oraib Toukan (2019) speaks of the legacy of discernability that images from Palestine have strived to preserve as “images of resistance” that must be “evidentiary and as clear as one can be with a sign” (p. 3). Against that, Toukan posits the task of “navigating outside of the optical sphere” as necessary to “transcend representation all together, into a sphere of political consciousness” (p. 3; original emphasis).

Here, again, the political capacity of the glitch embodied in its “radical potential” (El Zein, 2020, p. 44) as well as its “critical potential” (Menkman, 2011, p. 27) becomes extremely pertinent. Although Toukan (2019) does not overtly refer to glitches, she nonetheless underscores the importance of disrupting visual fields through the act of zooming in to “the level of the pixel-grain” (p. 3). However, her quest is driven by a need not to see violence, but to know it. Toukan (2019) asks, “what is a knowing through seeing that which is indecipherable?” (p. 4). Hers is a question that I would like to further ponder, for neither Toukan nor my article is interested in delivering inferences. In my reading of AlSalah’s method, I have referred to the limitations of what Toukan (2019) calls “the representational frame” and its direct tie to the logic of the “aspect-ratio” (p. 4). Nonetheless, I remain committed to AlSalah’s work in its potential to engage with and engender disruptions within the grid as well as the grain of images, by centring the active capacity of glitching. Echoing Azoulay (2019), to know differently entails doing differently, and to do differently demands that we, first and foremost, espouse loss as a practice of unlearning. Hence, probing return alongside loss through a dialectical poethics is an attempt to hold the ground open for an unremitting exploration with filmic rehearsals of return against finality, without flattening the structural situatedness – and not the merely situational – from which these visions of return, “re/de/compositions”, to use Ferreira da Silva and Bradley’s words (2021, p. 3), are arising.

This essay was originally published as Open Access under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial Licence in the following journal by the Edinburgh University Press:

Film-Philosophy, Volume 28 Issue 2, Page 248-268, ISSN Available Online Apr 2024

(https://doi.org/10.3366/film.2024.0268)

REFERENCES

Azoulay, A. A. (2019). Potential history: Unlearning imperialism. Verso.

Bradley, R., & Ferreira da Silva, D. (2021). Four theses on aesthetics. e-flu/ Journal, 120. https://www.e-flux.com/journal/120/416146/four-theses-on-aesthetics/

El Zein, R. (2020). To have many returns: Loss in the presence of others. World Records, 4, 41–54.

Estefan, K. (2020). Witnessing the worldly within the imperial commons: Yazan Khalili’s

Hiding Our Faces Like a Dancing Wind. World Records Journal, 4, 145–147.

Ferreira da Silva, D. (2014). Toward a black feminist poethics: The quest(ion) of blackness toward the end of the world. The Black Scholar, 44(2), 81–97. https://doi.org/10.1080/ 00064246.2014.11413690

Ferreira da Silva, D. (2016). Fractal thinking. Accessions, 2. https://accessions.org/article2/ fractal-thinking/

Ferreira da Silva, D. (2018). In the raw. e-flu/ Journal, 93. https://www.e-flux.com/journal/ 93/215795/in-the-raw/

Ferreira da Silva, D. (2020, December 3). Invisible\obliterating. Pass Journal. https:// passjournal.org/denise-ferreira-da-silva-invisibleobliterating/

Google Maps. (n.d.). Street view. Google.com. https://www.google.com/streetview/ explore/

Guillaume, A. (2022). Cultural apartheid: Israel’s erasure of Palestinian heritage in Gaza. Al-Haq.

Karmi, G. (2010). Foreword. In M. Sahibzada (Ed.), JNF colonising Palestine since 1901

(Vol. 1). Scottish Palestine Solidarity Campaign.

Leeb, S., Stakemeier, K., & Ferreira da Silva, D. (2019). An end to “this” world. Denise Ferreira da Silva interviewed by Susanne Leeb and Kerstin Stakemeier. Te/t Zur Kunst. https://www.textezurkunst.de/articles/interview-ferreira-da-silva/

Marks, L. (2015). Hanan al-cinema: Affections for the moving image. MIT Press.

Mende, D. (2020). The code of touch: Navigating beyond control, or, towards scalability and sociability. e-flu/ Journal, 109. https://www.e-flux.com/journal/ 109/331193/the-code-of-touch-navigating-beyond-control-or-towards-scalability-and- sociability/

Mende, D., & Holert, T. (2019). Editorial: “Navigation beyond vision, issue one”. e-flu/ Journal, 101. https://www.e-flux.com/journal/101/274019/editorial-navigation-beyond- vision-issue-one/

Menkman, R. (2010). Glitch studies manifesto. http://rosa-menkman.blogspot.com/ Menkman, R. (2011). The glitch moment(um). Institute of Network Cultures.

Mitchell, W. J. T. (2005). The surplus value of images. In What do pictures want? The lives and loves of images (pp. 76–109). University of Chicago Press.

Moten, F. (2016). A poetics of the undercommons. Sputnik & Fizzle. Moten, F. (2018). Stolen life. Duke University Press.

Online Etymology Dictionary. (2019). Navigate. Etymonline.com. https://www.etymonline. com/word/navigate

Russell, L. (2020). Glitch feminism: A manifesto. Verso.

Sasa, G. (2023). Oppressive pines: Uprooting Israeli green colonialism and implanting Palestinian A’wna. Politics, 43(2), 219–235.

Sharrock, J. (2013, April 11). Pegman: Google’s weird art project hidden in plain sight. Buzzfeed News. https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/justinesharrock/pegman- googles-weird-art-project-hidden-in-plain-sight

Spillers, H. J. (1987). Mama’s baby, papa’s maybe: An American grammar book. Diacritics, 7(2), 64–81.

Toukan, H. (2019). Toward a more navigable field. e-flu/ Journal, 101. https://www.e-flux. com/journal/101/272916/toward-a-more-navigable-field/

Wayne, M. (2020). Mar/ism goes to the movies. Routledge.

We Are Moving Stories. (2018, May). Kinodot Festival – Your father was born 100 years old, and so was the Nakba. We Are Moving Stories. http://www.wearemovingstories. com/we-are-moving-stories-films/2018/5/21/kinodot-festival-your-father-was-born-100- years-old-and-so-was-the-nakba-

Weheliye, A. G. (2014). Habeas viscus: Racializing assemblages, biopolitics, and black feminist theories of the human. Duke University Press.

Weheliye, A. G. (2019). Black life/schwarz-sein: Inhabitations of the flesh. In J. Drexler- Dreis & K. Justaert (Eds.), Beyond the doctrine of man: Decolonial visions of the human ( pp. 237–262). Fordham University Press.

𛲗⚭⚭⚭𛲇